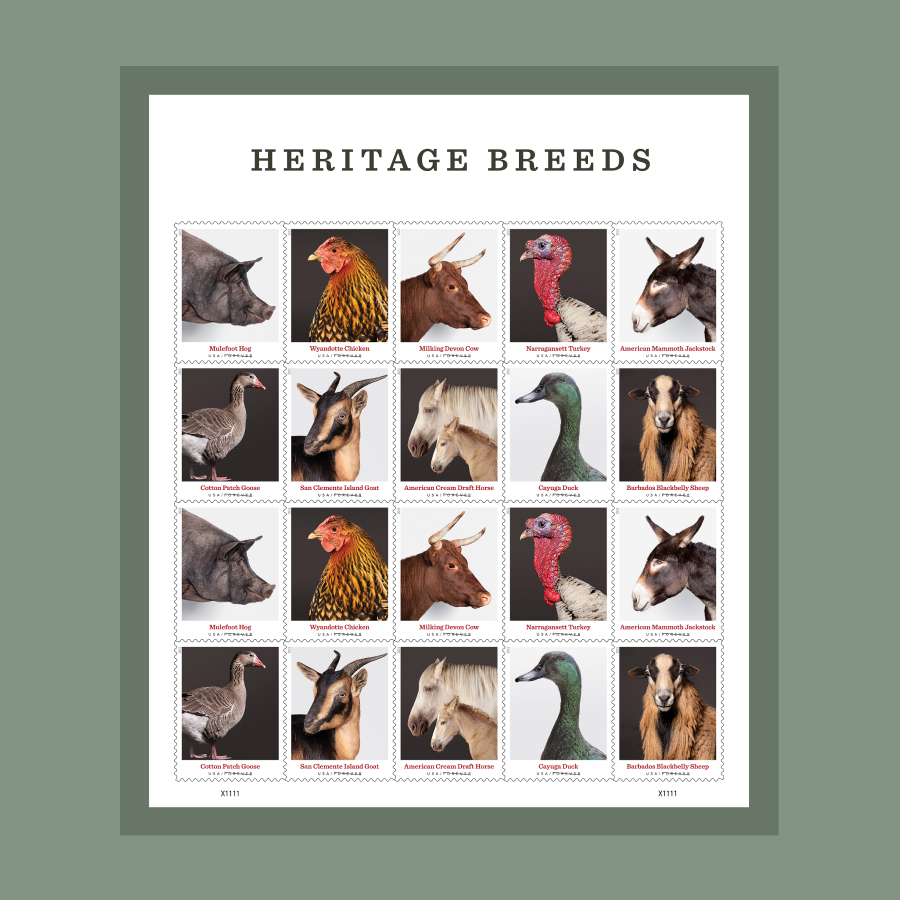

Heritage Breeds

Farm animals can be a much more controversial subject than you’d expect.

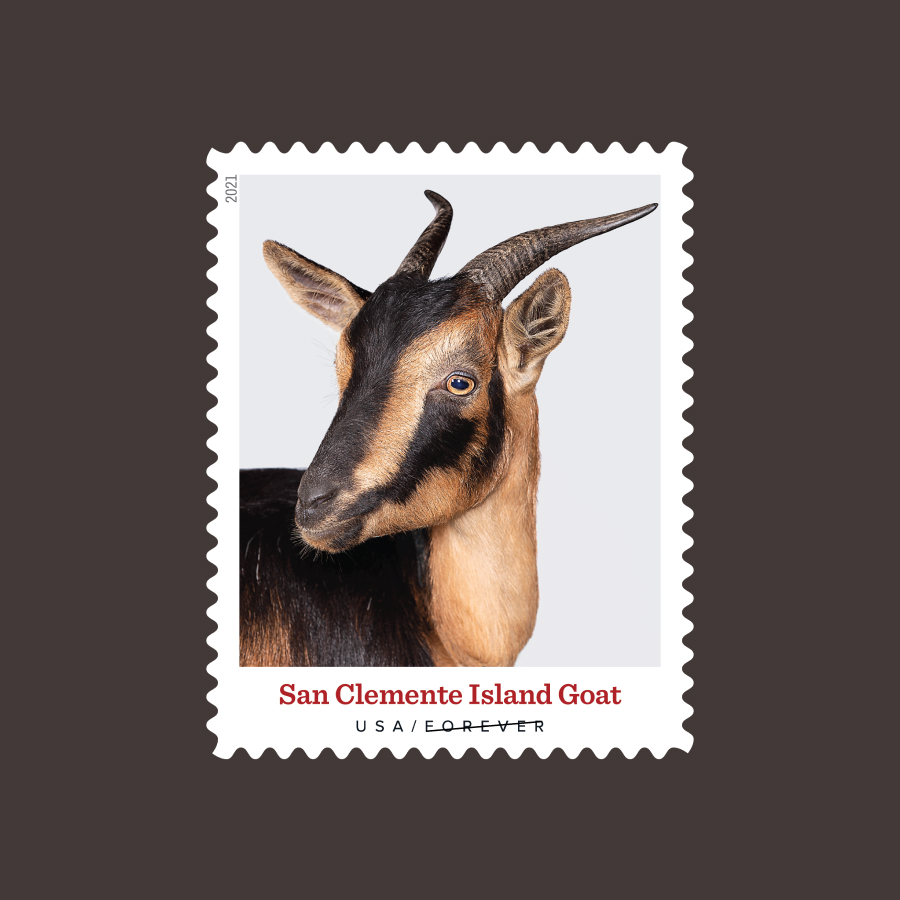

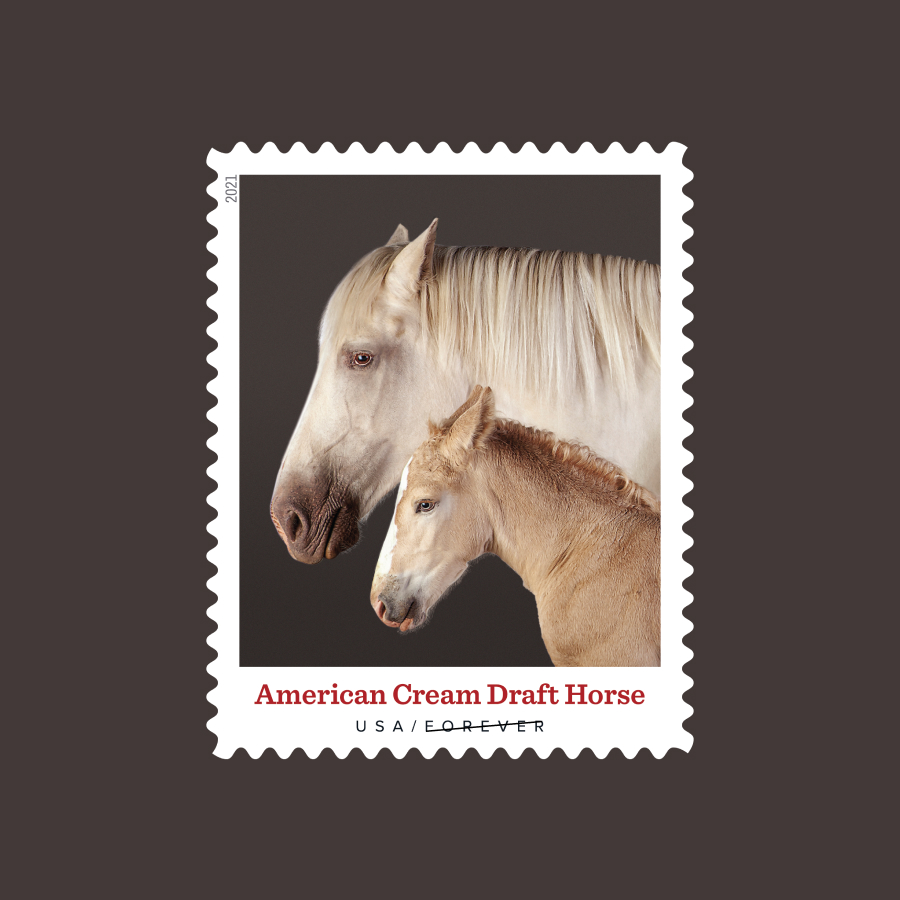

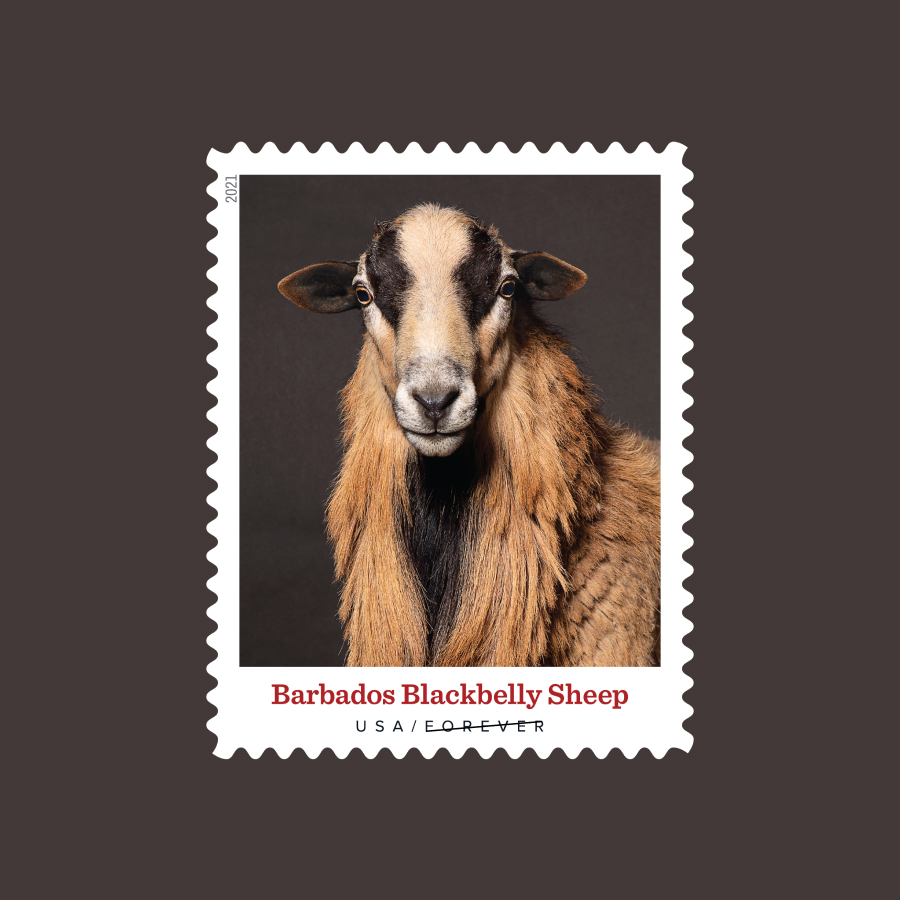

From hundreds of heritage breeds, stamp art director Greg Breeding and designer Zack Bryant took on the challenge of picking just ten to appear on a pane of stamps. Thankfully (or woefully, depending on how you look at it), they didn’t have to make that choice alone: They consulted with livestock experts, farmers, and stamp photographer Aliza Eliazarov, who captured the animals on film — often while lying in manure and muck to land the perfect shot.

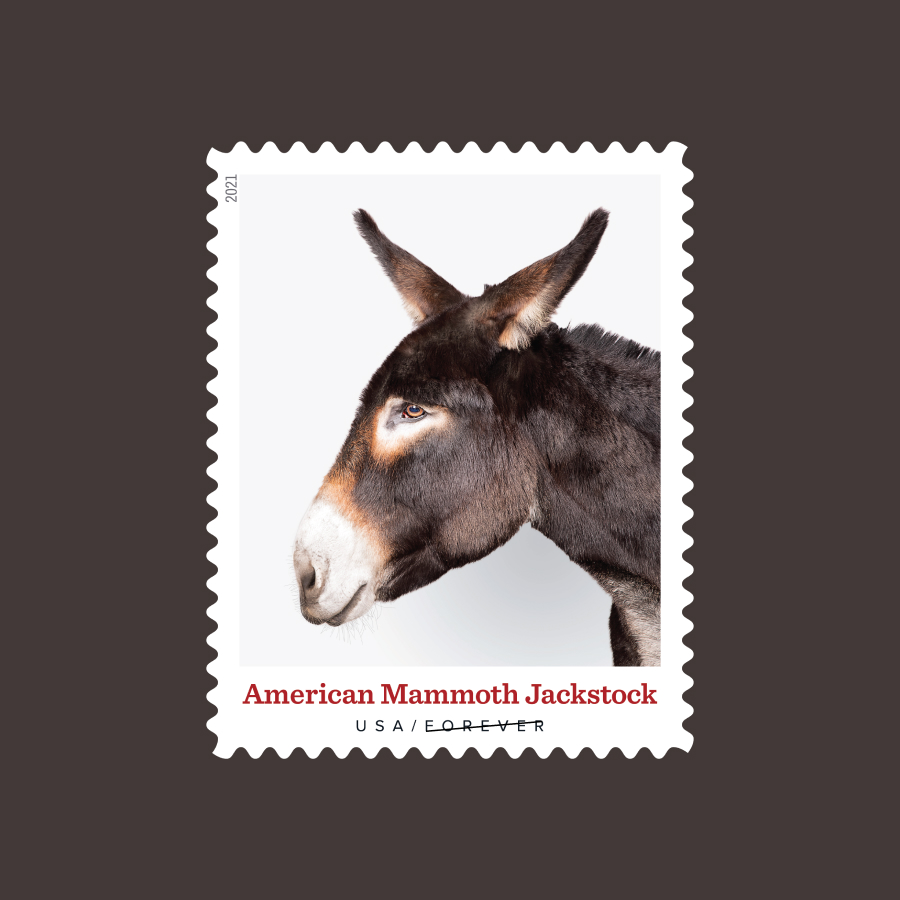

Should they choose a cow raised for milk or for beef? A draft horse or a quarter horse? A Tamworth pig or a Mulefoot hog? Everyone had an opinion. “It was fun, but it was a little chaotic,” Breeding says. “More than most of the projects I’ve worked on. Almost too many good options, in a way.”

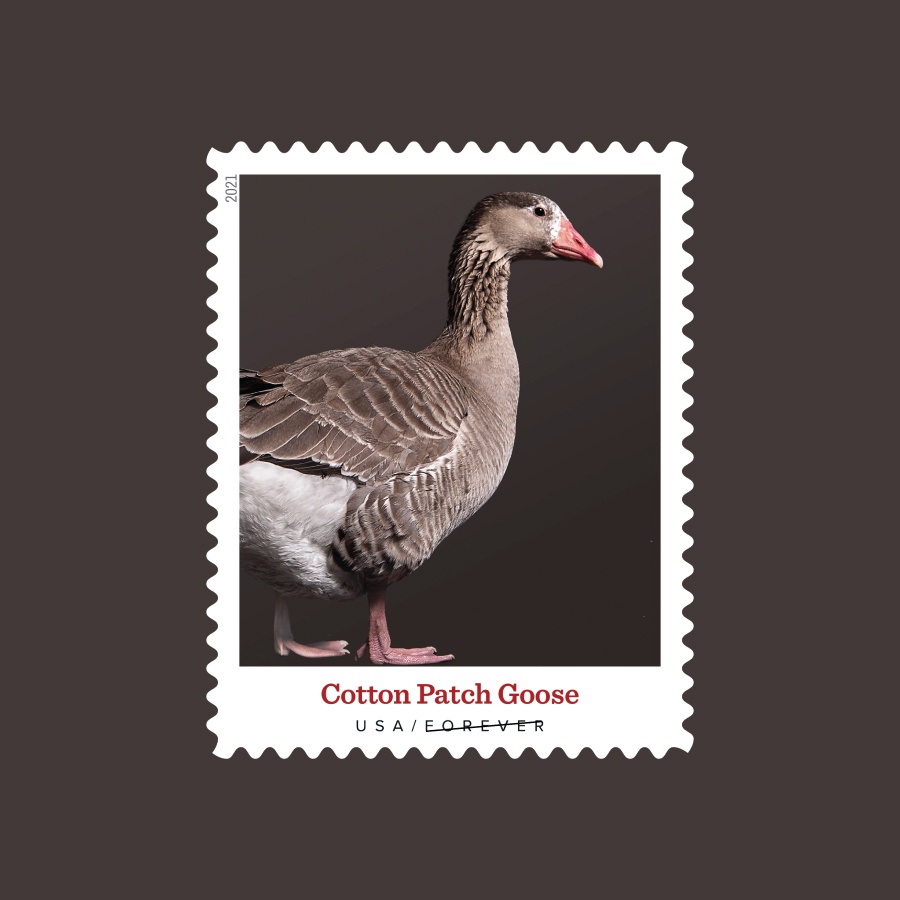

Many of the farm animals Americans know and love — such as the endearing pink Yorkshire pig or the white and fleecy Cotswold sheep — actually come from Britain, says Bryant. To narrow their choices, the stamp team focused on what he calls “New World breeds,” whose indigenous North American ancestors crossbred with animals brought over by the Spaniards. “It’s an interesting melting pot, if you can say such a thing exists for livestock,” Bryant says.

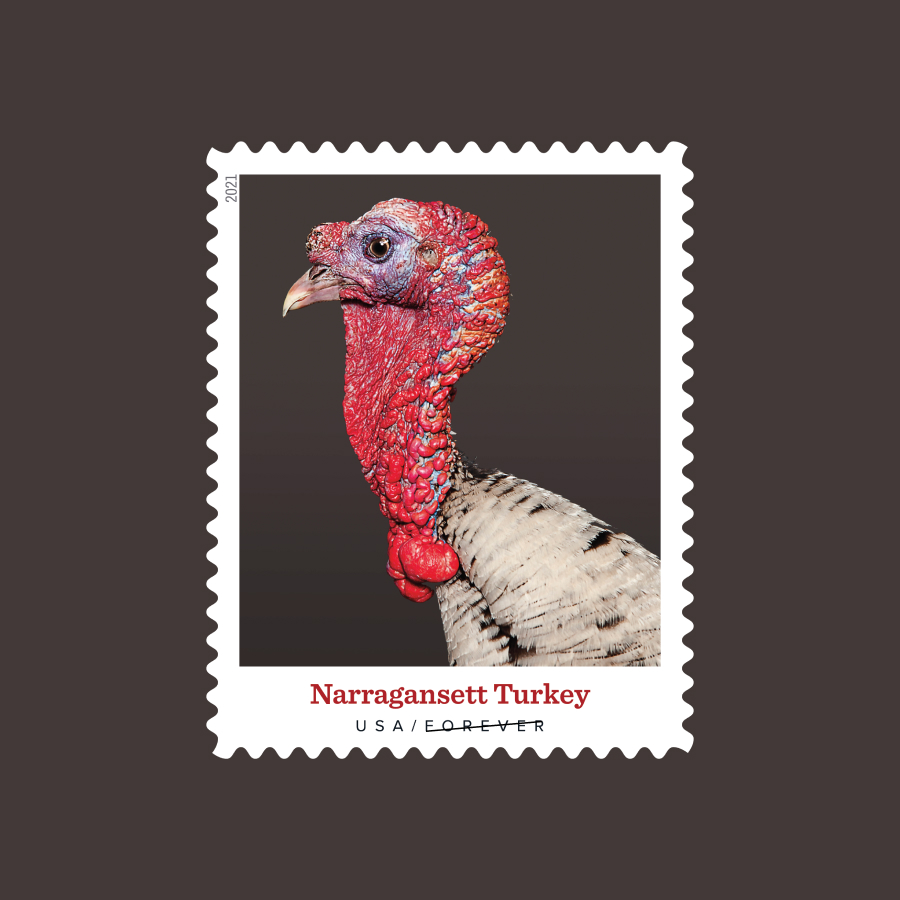

The team also selected breeds they thought many Americans might never have encountered before, cropping the photos closely to allow the animals’ pleasing and surprising eccentricities to shine. Bryant’s fondness for each is clear: He points out the “black eyeliner” on the Cayuga duck; the “golden, lacy feathering” around the neck of the Wyandotte chicken; and the blue and red wattle on the Narragansett turkey which, as with every turkey breed, is like a “mood ring,” he says — changing colors depending on the animal’s state. Some of those breeds were late additions; finding the stamps awash in browns and grays, Breeding suggested to Bryant that they bring in more color.

Even with reduced choices and design constraints, some disagreements were inevitable. The project was deeply personal for many of the people involved: Bryant runs a small farm of his own (he’s even raised Wyandotte chickens in the past), and Eliazarov adores every farm animal she encounters.

“Her own stamp pane is this thick,” Bryant says, holding up her 256-page book of farm photographs. Not to mention that many farming families whose animals she captured on film have been conserving a particular heritage breed for generations; Bryant says it was especially hard knowing that some of them wouldn’t see their animals represented.

Although it was impossible to include every single breed, the stamps pay a powerful tribute to the creatures that are helping many of us reconnect with both our food and our pre-industrial roots.

Bryant remembers a story Eliazarov shared from one of her photo shoots: two farmers who were “just beside themselves, not even that their animals might be on postage stamps, but that the Postal Service was making these stamps in the first place,” Bryant says.

“So many people are just happy that these animals are getting their moment in the spotlight.”